Can we really blame our cats for taking too many risks? Paul Crossland investigates.

Health and safety is often incorrectly used as a convenient excuse to stop what are essentially sensible activities going ahead. In the UK a few years ago, the Health and Safety Executive launched what it calls the Myth Busters Challenge Panel, to scrutinize decisions in the media and highlight how inappropriate this is to a wider audience.

Chaired by the HSE Chair, the Panel is supported by a pool of independent members who represent a wide range of interests. The Panel looks into complaints regarding the advice given by non-regulators such as insurance companies, the tabloid press and employers and quickly assess if a sensible and proportionate decision has been made. The HSE want to make clear that health and safety is about managing real risks properly, not being risk averse and stopping people getting on with their lives. Good risk management is very much an enabler of activities, not the reverse.

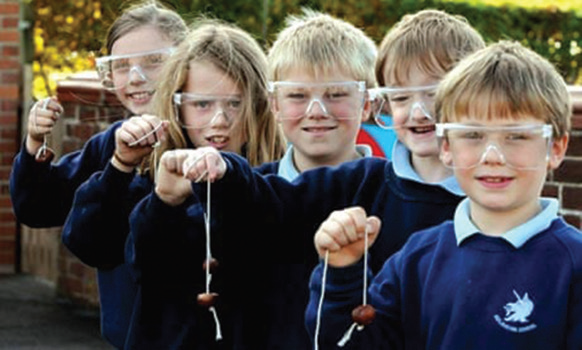

Check out this link on the BBC’s news pages for more details. This follows on the heels of my professional body, the Institute of Occupational Safety and Health’s (IOSH) decision to sponsor the annual World Conkers Championships, following a number of stories in the press a few years ago about kids having to wear goggles in school when playing conkers… (sigh).

Risk balance

I see all of this as a reaction to a lack of proportionality and a lack of “risk balance”. Life has been getting increasingly safe in the UK over the past 100 years; life expectancy for men and women is now around 80, in the main we’ve stopped putting small children up chimneys to clean them out, and no one has died of phosphorus poisoning in a match factory in the UK for decades as far as I’m aware.

In our vehicles we now have seatbelts, ABS, traction control, adaptive cruise control and many modern cars and trucks have much faster computerised brains than ours to apply the brakes when we’re too busy eating a sandwich or searching for our favourite song on our smartphone at 70mph to consider doing so. So the idea of “risk” has started becoming rather abstract, and we’ve invented new dangerous leisure pursuits to counteract this over-safe lifestyle; skydiving for fun (rather to invade another country), parkour (also known as free-running), downhill mountain bike racing, bungee jumping, I could go on. Part of this is an over-compensation, where any kind of risk (or “fun” as people like me, see it) is too much.

From the 1970s (since our beloved Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 came along) we’ve been used to pondering the phrase “as low as reasonably practicable” (or ALARP) when it came to assessing and managing risk. Let me break this down into its component parts, and you can try to picture any company-related safety problem you care to imagine in mind. Ready? Let’s go…

What is reasonably practicable?

“Practicable” means it can physically be done given limitless resources. Fair enough. If it can’t be done, then let’s not do it, right? OK, so far so good. If it can be done regardless of the cost, then it’s practicable. Let’s assume it can be done, and therefore a solution is practicable.

“Reasonable” next. If there’s little risk to life or limb, and to put it right will mean the organisation goes broke, it’s not reasonable to expect the organisation to spend lots of time and money trying to solve a problem that doesn’t need solving, and put itself out of business in the process. There’s a cost benefit element in “reasonable” and there always should be. This is still the real world isn’t it…?

So to be as low as reasonably practicable, we need to have a significant activity where someone is in danger of being hurt, possibly badly, and where we can reasonably be expected to provide a cost-effective solution to reduce the risk to a point where a person wouldn’t get hurt, if they were behaving normally. That’s risk management boiled down to its most basic form, and it doesn’t seem unreasonable to me.

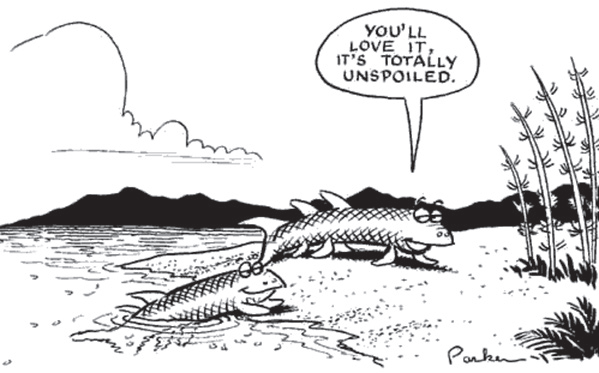

It’s also something we do every day. Ever crossed a road? Driven a car? Boarded a plane? Climbed a tree? Climbed up a ladder? Visited the dentist? You will have done some sort of risk assessment to decide whether to proceed, before each one. I know this to be true as you’re still alive. Well done! Your collective ancestors for the past 3.6 billion years would be very proud of you; you’re the pinnacle of their collective efforts not to get squashed / eaten by an Allosaur / hit by an asteroid / crushed by a steam train, infected by cholera, etc., leading up to today. Their “crawling onto land” moment was all worth it.

Anyone going through life blithely skipping along not weighting up the odds of their potential sudden demise doesn’t tend to live very long. Their ancestors are not a happy bunch, I can tell you; all that hard work for nothing.

What’s your acceptable level of risk?

John Adams postulated his theory in 1999 that everyone has their own “Risk Thermometer”. In essence this theory states that for any activity, a person has a certain level of acceptable (comfortable) risk, akin to a comfortable temperature range. If something is done to make the activity safer, the person will adjust their behavior to take more risks, bringing the overall risk level back up towards the maximum acceptable level. He famously demonstrated this in a study of seatbelts, which he said failed to save lives because belted drivers simply drove faster and more recklessly since they knew the seatbelts would help keep them safe. Before you get the idea that safety doesn’t work, Adams summarizes the theory as “the potential safety benefit gets consumed as a performance benefit”. In other words, safety measures don’t do nothing – they allow us to reap the benefits of taking more risks.

We need a risk balance in our lives, and yours will be different to everyone else’s; dependent on a wide range of factors including the two biggest – gender and age. It’s no surprise that the people with the biggest appetite for risk are men under 30. The ones pumped with adrenaline and testosterone, the hormones that goad us into taking risks and show how brave we are. So why is it so hard for some people to grasp that? I suggest that it’s because of a number of factors that have appeared in our society over the past generation:

- A creeping fear of being sued if something goes wrong. It’s something that’s come to us from the very litigious environment of the USA. If something happens, it SURELY must be someone else’s fault. Are you careless enough to spill your hot coffee in your lap and scald yourself? It’s not your fault, it’s the fault of the restaurant for giving you hot coffee when you asked for… er… hot coffee.

- A realisation that if you make enough fuss and noise people will probably pay you to shut up and go away. “Had an accident at work that wasn’t your fault? You’re owed thousands! Call 0800-SLEAZY for help. No Win, No Fee!”

- More and more detailed legislation and control over what we do at work and how we do it. There have been hundreds of new Regulations published in the UK in the past 40 years or so. Check out this list from the HSE if you have a moment. We have to abide by all of these or face prosecution, fines and a risk to our reputation. As a result, a new profession has sprung up; mine!

- And lastly, the one I think is of most concern – a failure to understand that making mistakes and having accidents teaches us to be more careful in future, because it hurts to fall and cut your knees. But we remember, and we learn and we change, and we do it better next time. This seems to be a powerful and necessary message that we’re in danger of losing sight of. As James Joyce once said – “A man’s mistakes are his portals of discovery”.

Striking a balance

I’m not saying that we should applaud someone who has an injury – far from it, but that this risk versus safety balance needs to be restored in society. Have a think for a moment – who are the people in life that we admire most? Are they the people who do very little at the risk of failure and therefore take no risks? Or are they the risk-takers, the innovators, those that excel, those that ask the awkward questions, those that do things differently and push the boundaries of what can be done? Felix Baumgartner, take a step forward….

At ITConsilium, a good safety culture needs to be one of our widely-published key values, and for very good reasons. It’s not just lip-service, but a core way of working. We must never lose sight of the fact that if we get our health and safety balance wrong, it can get in the way of us doing good business well. At the risk of yet another driving reference (and as a keen motorcyclist, this is really starting to worry me…) if we try to bolt it on to the business as something separate, it can be a useless 5th wheel. It needs to be one of our drivers for making our business work more efficiently, and making life a rewarding experience. One of the challenges in my role will be to make sure that we continue to develop a meaningful safety and wellbeing culture where we get the risk balance right. If you think we’re not getting it right, and that it’s getting in the way of you doing your job efficiently and safely, I want you to tell me. That way, I can try to change it and hopefully make your life that little bit easier.

As a little aside to this thread, do you have cats? Bear with me. Cats are prone to a parasitic infection called toxoplasma gondii. This is thought to infect 1,000 people a day in the UK through contact with infected cat litter (about 7% of the UK population; 68% in France).

Toxoplasma has been found to affect brain chemistry in rats (and chimps) leading to a reduced fear response to predators. This ensures the infected rats get eaten by cats, an essential part of the parasite’s lifecycle. It forms cysts in the amygdala, the region of the brain involved in registering fear. It’s also been found in a study of young motorbike racers in Spain, where almost 80% were found to be infected. It messes with the brain, changing brain chemistry, forcing us to take more risks. I’ve had cats all my life, and I’ve ridden motorbikes for over 35 years.

Ergo, my cats made me do it…