John Davidge argues the benefits and the drawbacks of technology in our vehicles.

The aim of the European Transport Safety Council has been to focus on halving road deaths by 2020 compared with 2010 levels, and some of that focus has been on using (and even mandating) better in-vehicle technology to aid this objective. On the face of it, that sounds like a great idea, since technology is getting more sophisticated, more reliable and less expensive all the time, and can perform more consistently than humans – for example, I’ve never yet heard of a computer falling asleep or getting distracted – have you?

But is there more to it than that? Consider for a moment the following aspects:

- Our mobile phones and computers have far more technology than we would ever expect to use, and many of us have little idea of some of the built-in capabilities that developers have spent hours creating. What about the technology in our latest vehicles?

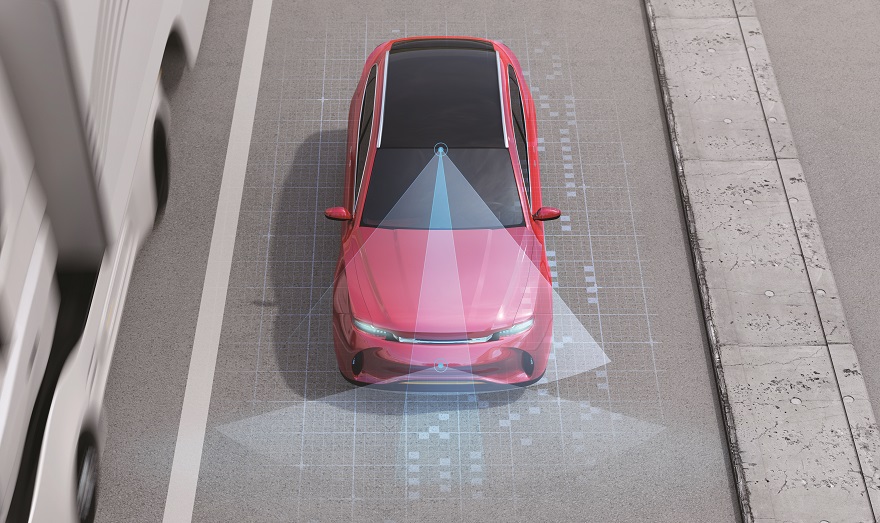

- Some of those capabilities are also questionable. For example, ‘Intelligent Speed Adaptation’ is a system that uses GPS location and speed limit databases to identify the speed limits that we are driving in, and will then take control to prevent us from exceeding those limits. If the system is that ‘Intelligent’, why does it then allow the user to override it, to turn it off? Surely those most likely to override it, are those who most need it and will benefit from it in protecting road users! Bizarre.

- How well do drivers know the functions and features of their vehicles? When my last lease car, a plug-in hybrid, was delivered by a major leasing company that I won’t embarrass, I was promised a full handover by the ‘delivery team.’ The reality was that when it arrived, and I asked the two guys to explain, to give me the promised ‘full handover’ the response was a blank stare, and a casual “S’a pretty colour, innit?!” before they disappeared rapidly. Not helpful to a driver who might not be quite so confident about a new vehicle.

Knowing the technology and features

We can equally imagine the dilemma of a company vehicle driver whose usual vehicle is in for extended repair, being told: “Look, just take that red one over there, the previous driver has left, and it will save us a fortune in hire vehicle charges until yours is back in action.” Later that day as the novice drives home through town and a cyclist wobbles around a pothole in front of him, when ‘City Safety’ or its equivalent rapidly and firmly apply the brakes in front of him to avoid a possible collision and leaving that driver in a shaken state. For the rest of his/her journey home and for the ensuing weekend it’s not difficult to envisage the driver nervously awaiting the next shock.

As we move towards the arrival of the fully autonomous car that everyone (apart from me) is so sure is just around the corner I’m sure that some drivers will programme it to just ‘get me there’ and promptly get on with other tasks. Whilst we know that drivers typically take much longer than the average Highway Code reaction time of 0.68 second, it’s not difficult to see that the autonomous ‘non- driver’ who is busy updating social media (sorry, working online!) will take a lot more time than that and in a situation where the human needs to take over from the car the true reaction time may well be far more than we think – by which time the impact has probably happened. With more and more ‘connected’ cars, perhaps the next step is for a new driver to sign in to the vehicle with username and password, to take a short online (sorry, on-dashboard!) e-learning with tests that the driver must pass, before being allowed to move to the next module (to start it and drive it!).

Has adequate training been given to use the technology and drive safely?

Back to present day, the Provision and Use of Work Equipment Regulations already expect and require every employer to use only the right equipment, be sure it is in good order, and ensure that it is only used by a person who is adequately trained in its use. What does ‘adequate training’ look like? In my example above, would the ‘proper vehicle familiarisation and handover’ have been adequate in a court of law? I’m not sure it would, are you?

More than thirty years ago, a major UK petroleum company changed from using Scania 3-series tankers to Scania 4-series – the changeover also involved moving from 2-axle tractors to 3-axle, from metal springs to air suspension, and to a more powerful engine and higher weight limits. Every driver went through internal vehicle familiarisation training before being allowed to drive the new vehicles, and once trained was never permitted to drive the 3-series again (with all the older style vehicles being taken away from that depot in each case, once all drivers were trained). Naturally, the possible outcomes of a major collision involving a petrol tanker are substantial but when we look at the principles, how many other companies do you know that have ever undertaken anything like this? Similarly, airline pilots must undertake specific ‘aircraft ‘type’ training before moving to a new aircraft.

Against that background, the general principle of the Health & Safety at Work Act looks for employers to ‘ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the …safety and well-being… of employees and others…’. And with subsequent regulations requiring ‘suitable risk assessments’ and the provision of ‘appropriate training.’ I can envisage a situation where someone is injured on the road, complaining that ‘the company caused it, they gave me this car and didn’t show me how to use it properly’. Isn’t it a normal typical human response to look to blame someone or something else when things go wrong? Even some seemingly simple aspects could catch out the unwary – on a vehicle with an electric handbrake (sorry, parking brake!) which releases automatically, does it apply itself automatically too? Or does the driver have to apply it each time manually? One wrong assumption by a driver could see a driverless vehicle rolling down a hill and colliding with vehicles/people – that is food for thought.

Nothing is so important that we cannot take the time to do things safely

The question, therefore, must be, ‘can you be sure that when a driver is given a different and very modern vehicle to drive, that the assessment and training that you give, was enough to satisfy a judge and jury in the Crown Courts that you had done so, so far as is reasonably practicable?’

And more importantly, if so, can you prove it successfully in a court of law? In the absence of any documentary proof, courts tend to assume no such training was provided (possibly on the basis that if it had been provided, the collision would not have happened).

Driving is still the most dangerous activity that we undertake – and that is usually because we assume wrongly that it isn’t, so we take things for granted.

Our nationwide network of qualified assessors can help develop your drivers, improve their driving skills and reduce the risk of accidents.

See how our in-vehicle driver training can help drivers in your company. Email [email protected] or call 020 4769 0200 for more information.