With screen-time increasing, it’s time to ask some important questions around the way screen addiction could impact our future workforce, says Stephen Smith.

In 2014 app developer Kevin Holesh moved in with his fiancée. After a hard day at work they would settle down on their couch with their smart phones in hand and lose themselves for a while. Initially, this gave them a chance to unwind, to relax, and drown in the ludic joy of the screen’s calming glow. However, it also took up precious time. Kevin realised that less and less of their spare time was spent in productive leisure, or even doing anything exciting, but instead simply fixated on the screen.

After living in distraction for six months, Kevin realised that there was a problem and that he was ‘addicted’ to his phone. So he decided to come up with a solution in a way only he knew how. He was going to design a mobile app to combat his addiction to the mobile phone.

The app eventually became Moment. Moment is a tracking app for mobile phone use. It sits silently on your phone, discreetly tracking your usage and totting up the hours you’ve spent and the activities you’ve carried out on the device.

When he started he found that he was using his phone for approximately 75 minutes every day. Now he’s limited that to just 45 minutes a day. This app is now available on iOS and Android and comes with a bunch of paid-for features that can help you limit this neurological time-drain.

But that’s not the whole story. Let’s see what else this we can learn here.

Technological addiction

In early 2017 Adam Alter, Associate Professor at New York University’s Stern School of Business, released his book Irresistible: The Rise of Addictive Technology and the Business of Keeping Us Hooked. His work aimed to expose the underlying psychological and behavioural triggers that have seen mobile phone use and on-screen time increase (now, on average, Americans spend 10 hours and 39 minutes each day across all screens ).

A couple of years ago Adam realised that he was spending too much time on his phone, and was looking for a way to limit it. He could see the impact it was having on his life and how much time was being eaten up by it. So, searching around one day, he found Moment.

Tracked across thousands of Moment users, a picture of our technological addiction, and its increased prevalence, begins to build up. Two years ago, the average time spent on mobile phones was 2 hours and 48 minutes. In 2017 this rose to a whopping 3 hours and 42 minutes . That’s nearly 4 hours in every 24.

However, I grant you, the figure might not be that alarming. We have plenty of free time, so how’s a little skip through Facebook every now and then going to hurt us?

Work, rest and screen-time

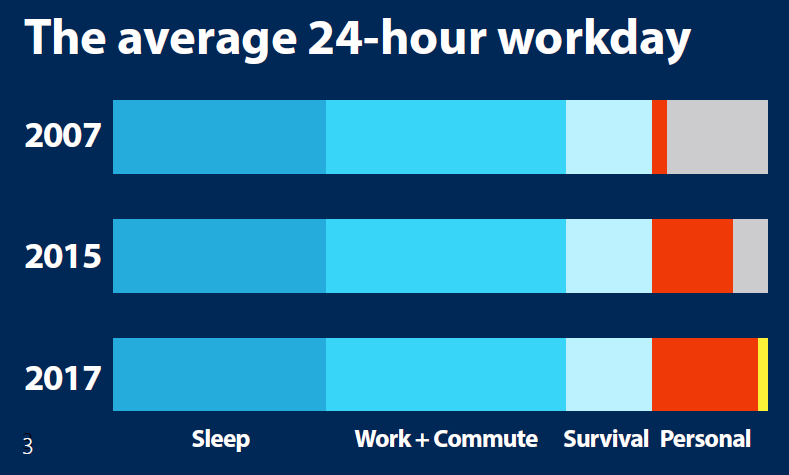

This chart, taken from Adam’s recent Ted Talk, shows the estimates of how much time is taken up doing things across the average 24 hour day.

The blues shades focus on our core daily activities, like going to work, sleeping, cooking, eating and other survival and necessary activities. White and yellow highlights free time, while the red shows the burgeoning, all conquering tide of screen-time.

In his book, Adam calls this an addiction. The American Society of Addiction Medicine defines it as such: “A primary, chronic disease of brain reward… this is reflected in an individual pathologically pursuing reward and/or relief by substance use other behaviors”, causing “significant problems with one’s behaviors and interpersonal relationships ”.

In this case, not only is it an activity that takes up is characterised by brain reward, but it’s damaging the relationships we have with people. Indeed, his main concern is a social one, that more and more screen-time will lead to isolation, an inability to adequately interact socially, and ultimately depression.

Good app, bad app

There is an upside though. Thankfully, all that disappearing free time isn’t just used up fruitlessly spinning from one app to another. Smart phones are incredibly useful. They help us navigate the world anew, with fresh perspectives and un-blinkered eyes, they connect us and bind us, and bring new insights and information with a minimum of difficulty.

Adam’s research shows that we spend an average of 9 minutes per day on healthy, constructive apps that enrich us. However, he warns, 27 minutes per day is taken up on the types of damaging apps that cause fear, isolation and depression, like social media and news sites. A much larger figure than healthy app use.

Ludic loops and stopping cues

The question remains, if the outcome of spending so much time glued to mobile phones is likely to damage us, then why do we spend so much time doing it?

Research over a 10 period by Natasha Dow Schüll, a cultural anthropologist from MIT, into highly addictive Las Vegas slot machines discovered that people enjoyed the game despite the low chance of success and repetitive nature of the activity. In fact, she discovered, heavy users were actually disappointed to win, precisely because it broke the repetitiveness of the game . She called the lulling, dream-like state of pleasure aroused by these types of games a ‘ludic loop’. The loop in question being the pathway, littered with small rewards, that gently nudges you to pull a lever here, a button there, but always with the view to keep you playing.

Schüll eventually associated her ludic loop to popular smart phone games, such as Candy Crush. In an interview with NPR she characterised the game in this way: “It’s you and the machine… there’s no real character development or narrative arc. Kill the monster; kill the monster again; kill the monster again. You never know when you’re going to get the reward [or] how much the reward will be. It’s these little ludic loops.”

We’ve probably all played these games at one time or another and found ourselves looking up at the clock to notice another thirty minutes has gone by. But it’s not just games that utilise the ludic loop formula. The entire design paradigm of our mobile phones encompasses this exact type of thinking.

Common ludic loops are those time-wasting activities that go unnoticed. I might check Facebook for instance, and then once I’ve had my fill, close that app and move on to Instagram. From there, I might go to Twitter and then after that, refresh my email and see if anything has popped up there. Once I’ve completed one loop, I might head back to Facebook and do it all again. The type of design that enables this unconscious looping is the part of the reason why we can easily spend upwards of 4 hours every day on their mobile phones.

Design it out

Adam Atler gives further analysis by talking about stopping cues. Newspapers, books, even television shows, have natural stopping cues. Once you get to the last page of the book, there’s nowhere else to go. Once you’ve been through a newspaper cover to cover, there’s nothing more to read. A television show lasts 30 minutes and once it’s done, that’s it.

The problem with apps is that they’ve been designed to reduce the number or visibility of stopping cues.

Take Facebook. The newsfeed is designed to keep throwing out more and more consumptive material to keep you engaged at all times. So too with online newspapers, particularly live-feeds on political or sporting events. And again with modern streaming services, such as Netflix. They now have technology in-built to play the next episode of the series, or related shows or films, so that you never have to think, you just sit back and let Netflix take you on the journey.

Young people and screen addiction

It seems that society’s youngsters are using their phones more and more. In an interview Adam Atler describes how, at the start of every new class, he gets his students to download Moment to track how often they use their phones.

Incredibly, he says, most of his students are using their phones between 6 – 10 hours per day!

Adam remarks that, along with sleeping and all the other necessary survival activities, there’s not even enough time to fit that many hours in without them being on the phone during his lessons.

Although studies have not yet given us the data we need on this, a recent study shows that average US smart phone screen time over 30 days corroborates Moment’s claim and puts it at 3.7 minutes per hour.

But I don’t think we can ignore anecdotal evidence as given by Atler. Screen-time seems to be on the rise, especially for the young.

Neuroplasticity

But, why does it matter that young people have grossly high levels of screen-time? Well, neuroplasticity, the term that describes how our brain changes over time, is the key factor. Our brains change throughout our lives. The neurological structures, the architecture of our brain and by extension, our thoughts, are changing through internet use.

Some have spoken about IAD (Internet Addiction Disorder) . Studies into this disorder show that the brain has responded to society’s growing internet use in ways that are similar to other addictions.

The authors of the study, Dr Hao Lei and colleagues, write: “Overall, our findings indicate that IAD has abnormal white matter integrity in brain regions involving emotional generation and processing, executive attention, decision making and cognitive control.”

With increased screen-time, the impacts on the brain could be incredibly dangerous. There’s evidence that excessive screen-time in early life can change the circuits in developing brains . This sort of rewiring could have large impacts on young people’s ability to focus, to process information, to make decisions and more.

Leah Krubitzer, an evolutionary neurobiologist, takes a different view on the negative case spelled out above. She states that there could be positive effects, especially in our over-stimulated sensory world. Young people could have greater resilience to multiple attention-seeking triggers, which could be useful in a world with ever more stimuli attempting to distract us.

“Less than 300 years ago we had an industrial revolution and today we’re using mobile phones and we interact on a regular basis with machines… There’s a tendency to think of the good old days, when you were a kid, and [say], ‘I didn’t do that and I didn’t have TV and look how great I turned out.”

However, without the appropriate studies, we’re yet to fully understand, or grasp, the impact of this huge societal change that is bound to cause fluctuations and ripples at a greater pace than ever before.

Business needs and the future

For businesses, understanding the impacts of this societal change and how the younger workforce could be affected by this addiction will be vital. Cardinus have already highlighted how future workforces could be afflicted by the physical effects of mobile phone use, in previous articles like Generation Pain and Ergonomics Tsunami. We have also spent a lot time putting together free resources for parents and young people, including a website, app and downloadable PDFs. But very little time and effort in our industry has been spent on the psychological impacts of smart phone use.

Understandably, we’ve shied away from discussing it as less is known about the future impacts. Indeed, as Krubitzer points out, it could all be fine and we’re fretting about nothing. But what we do know is that the brain adapts to the stimuli it is given, and if that’s almost entirely screen-based, then that’s something that has never happened before. The fallout could be dramatic.

From Adam Atler’s point of view, he’s worried about the social impacts of this change. That young people may not be getting the right kind of face-to-face stimulus required to cultivate and retain meaningful relationships. He goes as far as to suggest that, in years hence, we might view it with the same kind of health risk as smoking and that it could eventually become a regulated resource.

Right now, there’s no appetite for that, or the scientific evidence to back it up, but the suggestion does belie the gravity with which Adam sees this change. Businesses should take heed and keep an eye out on their younger population.

My own Moment stats

When I began researching into this article I decided that I should open the door on my own screen-time usage, and so, I downloaded Moment. Here’s my stats.

Average screen time: 1hr 25 minutes

Pickups – 40

I was astounded that I used my phone that much. I don’t even recall using it for any length of time, and I didn’t even ring anybody on the day in question, so that is all app-based usage. My aim is to bring it down to around 40 minutes per day, but I have no idea how!

Stephen Smith is a Marketing Executive at Cardinus. He has worked in marketing for a little over 4 years

and has written for numerous publications. He has a Master’s in Philosophy and enjoys long walks in the country.

References and further reading:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GwHIVJEdUbY

https://www.shortlist.com/news/psychologist-free-time-computer-screen/59174

https://medium.com/thrive-global/im-addicted-to-my-iphone-4b9601e2776f

https://lifehacker.com/use-the-stopping-rule-to-break-your-social-media-loop-1793016571

http://davidrainoshek.com/2013/06/how-facebook-fb-is-altering-your-mind-2/

https://edition.cnn.com/2016/06/30/health/americans-screen-time-nielsen/index.html

https://www.news.iastate.edu/news/2014/03/31/parentalmonitoring